Luke 15 Explained: The Hidden Layers of the Prodigal Son Parable

The Prodigal Sons

In Luke 15:11-32, the parable of the two lost sons isn't just a feel-good tale, it's a pointed response to real-life grumbling. Picture the scene: Pharisees and scribes muttering because Jesus shares meals with "sinners" and tax collectors (Luke 15:1-2). Right there, Jesus launches into three stories about lost things being found, with this one as the grand finale.

This parable fits in Luke's "travel narrative" (9:51-19:27), where Jesus journeys to Jerusalem, teaching about God's passion for the overlooked, the poor, the outcasts, the broken. Themes weave through like threads: wasting what's precious (the same Greek word in 15:13 for the son's squandering and 16:1 for the shady manager), and complaining when grace surprises (echoing the vineyard workers in Matthew 20:11). Luke masterfully brackets the chapter: it starts with religious leaders griping and ends with the older brother doing the same (verses 29-30). That "lost and found" chorus (verses 24, 32) rings out, tying into Luke's core message, true turning back to God and the kingdom as a joyful banquet (like Luke 14:15-24).

A key question rises to the surface: Is this one story or two? Some split it, the wild child versus the bitter brother, but it's unified around lostness. The younger's rebellion is loud and clear; the older's resentment simmers quietly at home. Without both, we miss Jesus' jab at self-righteousness, aimed straight at those Pharisees (Snodgrass 2008, 120-23; Bailey 1983, 88-113).

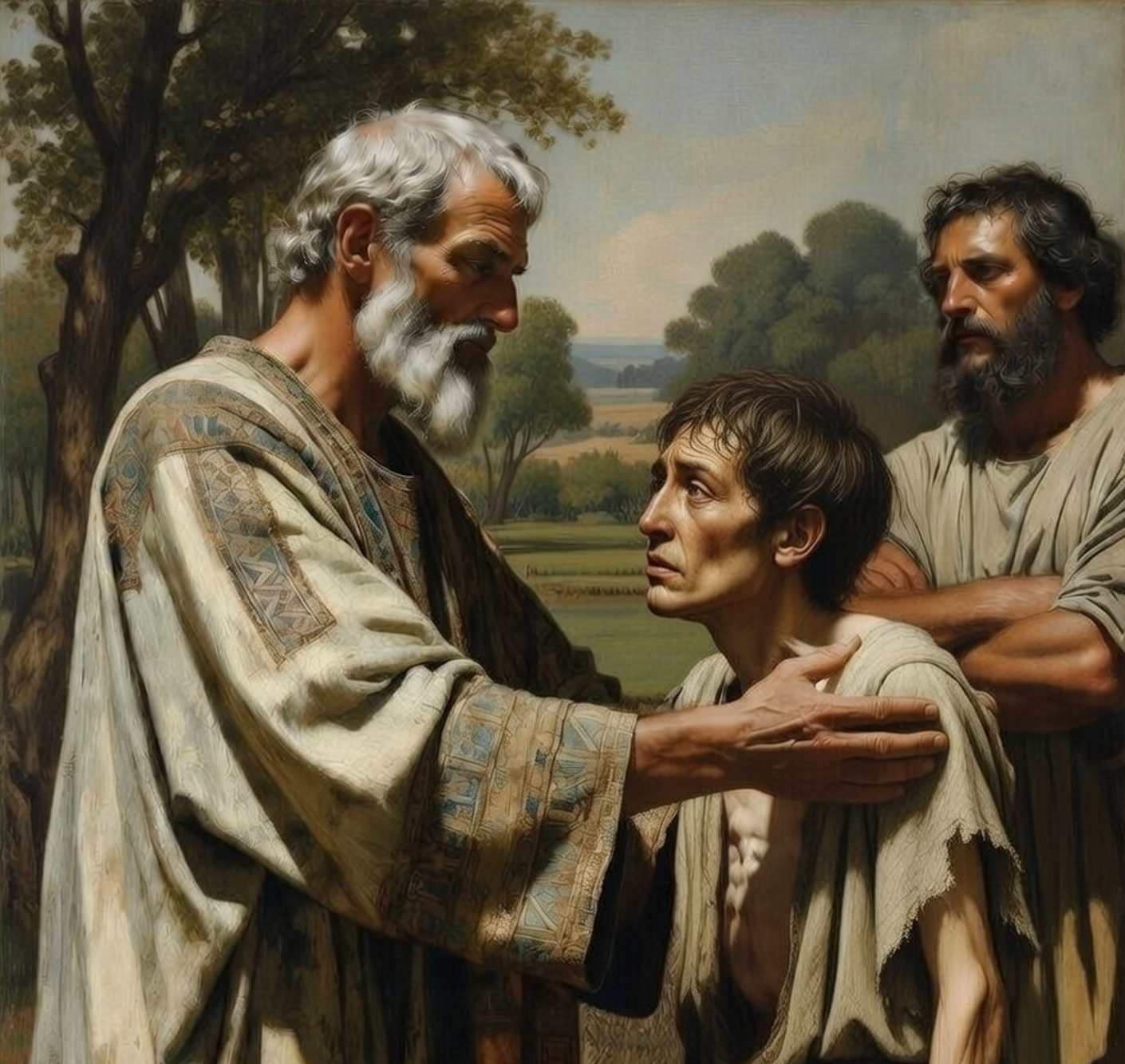

It is helpful to handle the characters gently. The father echoes God's tender care (Isaiah 63:16; Jeremiah 31:20), but it's no rigid code. The sons stand for sinners and the "religious," yet details like the robe and ring speak of restored honor, not deep doctrine.

The father's shocking kindness, running (undignified!), forgiving before full confession, flips expectations, showing grace rushes ahead of repentance (Snodgrass 2008, 128-30; Bailey 1983, 161-62).

Old Testament whispers add richness: inheritance laws (Deuteronomy 21:17) make the demand feel like wishing Dad dead; tales like Joseph's exile (Genesis 37-50) and God's aching love (Jeremiah 31:20) pulse through. Ezekiel 34's Shepherd-God seeking scattered Israel links to Luke 15's theme (Mishnah 1933, Bava Batra 8:7). Even Greco-Roman writers like Dio Chrysostom highlight family honor's fragility, while rabbinic tales contrast dutiful and repentant sons, stressing true return (Song of Songs Rabbah 1939, 1.7.3; Dio Chrysostom 1939, 30.22-25).

Luke's style is apparent: pairing men-women stories shows inclusivity; shared phrases (15:11 and 16:1) connect; the open end, does the elder join?, mirrors the Pharisees' choice (Snodgrass 2008, 124-26; Hultgren 2000, 75-76). Culturally, pig-feeding (unclean, Leviticus 11) is utter shame; the father's run and feast scream extravagant welcome; the elder's "slave" talk (verse 29) reveals inner chains (Snodgrass 2008, 131-35; Bailey 1983, 100-102).

These layers point to Christ, the Shepherd who seeks the lost (John 10:11). He ate with sinners to show the kingdom's open door (Luke 19:10). Where are we lost today, far off or close but cold? I want to let Jesus' pursuit melt my heart. I want to turn, join the party, and extend that grace to others.